Chapter Outline Cambodia 2000: The AIDS Year 6 March 2024

Fish traps and ricefields

Preface

A dream called me to Asia. I volunteered with AVI as a nurse in Cambodia. It was the worst AIDS epidemic in Asia with 30 to 50% sex-workers HIV positive while 60% of Khmer men went to brothels. Despite the challenges Cambodia turned it around, one of three countries worldwide to do so. The main strategy used was community mobilisation. HIV/AIDS is remerging in the South Pacific particularly in Fiji. The South Pacific UN AIDS Officer calls it a ticking time bomb. Again, community mobilisation is needed.

Chapter One, Arrival, Overwhelmed.

I arrived in Phnom Penh in March 2000 for one week’s orientation. The scale of corruption and the epidemic were overwhelming. I was sent to work in the epicentre, Poipet. When I arrived in Sisophon, my base, it felt like the ends of the earth.

Chapter Two, A whirlwind, Sisophon, sick generals, Sarin, Poipet and the dream.

I had a kind host but a hostile work reception. I visited sick generals with an army nurse and employed a local midwife, Sarin. In Poipet- I saw the poverty, the trafficking, the sex workers, and in a rural village I met the women from my dream.

Cargo haulers Poipet

Eating out in Sisophon

Chapter Three, Confronting reality, Battambang, a horrifying hospital, most villages affected and planning the next step

In a Battambang temple I tended a dying 20-year-old. After attending an ineffective workshop, I was taken to a horrifying Provincial hospital. A survey with Sarin showed most villages of around 600 people had 2 to 5 sick with AIDS and 2 to 5 who had died. There was widespread fear and ignorance.

Chapter Four, My Cambodian home, Khmer New Year- picnic at at temple, lack of coverage, turning a corner in Phnom Penh and the team celebrate my birthday in Poipet.

I moved into my own house. At Chinese New Year I picnicked at a temple with Sarin and her family. A provincial stakeholder’s meeting showed very few people were doing anything. The Director of the Provincial AIDS Office, Sin Eap and I set up a technical working group. In Phnom Penh their attitude had changed. I celebrated my birthday in Poipet with some of the team, national and local.

Chapter Five, Thma Puok Hospital, Edith and the cranes.

I visited the MSF Hospital on the Thai border in Thma Puok. There were deaths from multidrug resistant malaria and AIDS. Edith, a fellow volunteer, arrived. We visited the endangered sarus cranes at reservoir built during Pol Pot’s time and I later met one of the men who built it.

Skulls in temple

Chapter Six, Thai Temple of AIDS, evictions Poipet, Boueng Trakoun & high AIDS cases

At the Thai temple which cared for AIDS victims I saw the sadness of HIV positive Thai youths abandoned by families watching others die. 80 families in Poipet were evicted by the army to an isolated mud plain which hadn’t been demined. I toured the Thai border near Thma Puok and visited a village Boueng Trakoun with 2 newly appointed District AIDS Officers. We were told by the chiefs there were 90 people with AIDS out of a population of 9000. The District AIDS Director agreed to do survey.

Chapter Seven, Meeting Boeung Trakoun, Sihanoukville brothels and 100% Condom Program

We held a meeting in Boeung Trakoun with village chiefs, teachers, police, and monks, nurses and together we decided on an approach. Team flew to Sihanoukville for demonstration of 100% condom program in brothels and in readiness for introduction in Banteay Meanchey.

Chapter Eight, Festival of the Dead, Pailin

For the Festival of the Dead in Sisophon, I prayed, took food to the monks and biscuits to the orphans. I was invited to Pailin, a former Khmer Rouge stronghold where I toured hospitals, clinics, brothels, and border areas. I admired the independent and forthright women. I never returned as they secured funds and began a 100% condom program. Pailin thrived after it was demined.

Chapter Nine Family tragedy, Phnom Penh- Water Festival, Bokor Hill Fort, home for Xmas.

A teenage friend of my son completed suicide and I wanted to leave. I had to go to Phnom Penh to call the family. I was very relieved to find they were OK and they wanted me to continue my work. There were a million extra people in Phnom Penh for the water festival with 60 seater boats racing. I took a break and went up to the Bokor Hill Fort on the back of motorbike. 1000 Khmers died building the road. At the top was a ruined hotel and church full of bullet holes where the Vietnamese fought the Khmer Rouge. The sea was thousands of metres below. I flew home for Xmas.

Chapter Ten, Weekend with Edith, Poipet evictions and Human Rights

When I returned, I attended an NGO network meeting and was invited to Malai, a former Khmer Rouge district. On Sunday Edith and I walked with the orphans to a hill temple cave. At a UN party I learnt a special UN Envoy was visiting Poipet to investigate the forced evictions by the army.

Chapter Eleven, Thma Puok -TB and sick infants, Chinese New Year- picnic, marriage without romance,

When I visited Thmar Puok hospital there were many patients with TB and many sick infants. In 2001 two thirds of Khmers had TB, and one in ten infants died before 12 months-mainly of respiratory disease and diarrhoea. On Chinese New Year I went on for a picnic with Sopheak, Sarin’s niece who was now working with me. My language tutor said only the west believed in romance and marriage.

Author at Ta Prohm

Chapter Twelve, A visitor, Siem Reap and my Khmer self.

I picked up an Australian visitor and we went to Siem Reap. Angkor Wat was gloomy inside but romantic at sunset. The Bayon with two hundred faces of the Buddha of Compassion was my favourite, together with Banteay Srei, the temple of women. After returning to Sisophon we visited the District Hospital in Mongol Borei, the horrific hospital I had visited previously. There was a dramatic improvement. It was clean and well-staffed. My visitor told me how Khmer I had become, and how I would have difficulty adjusting back to Australia.

Chapter Thirteen, Malai- Khmer Rouge, Mines TB and malaria, Sampov Loun- brothels and trafficking.

Like Pailin, Malai was the most heavily mined area on earth and people were poor. At the hospital the main problems were mine injuries, TB and malaria and there were AIDS deaths. I visited Sampov Loun a border town notorious for trafficking. Malai prospered after it was demined.

Chapter Fourteen, Treatment at last-USAID, Chinese Tomb Sweeping Day, UNICEF funds Thma Puok, Sarin’s baby, Fire and 4 deaths

15th March, critical tour with USAID reps. Over the next five years they spent $US1.5 million for 3 clinics which provided anti-retroviral treatment and dropped the mortality by half. On tomb sweeping day, with Sarin’s family, we drove by truck to the family graves, we prayed, and shared a suckling pig with the dead. UNICEF agreed to fund a project in Thma Puok- Health services there were improving. Sarin gave birth to a boy- they were ‘roasting’ and looked very hot. A fire in Sisophon destroyed 24 houses while 4 people died. It was lit by a jilted lover who was jailed. The fire truck had been sold.

Chapter Fifteen, Khmer New Year, orphans and mistreated children, sweethearts, EMPOWER- sex workers, the overlooked group of 8000 soldiers.

My guard told me stories about broken families, where sometimes the children were sold. With the epidemic there were also a growing number of orphans, 55,000 nationally. HIV transmission between husbands and wives increased because men were increasingly turning to ‘sweethearts’. Only one third of men wore condoms with them. Husband to wife transmission accounted for almost half the new cases in 2002. My colleagues and I including Eap, went nightclubbing with Thai sex workers who held workshops for the locals including lap dancing. We identified 8000 unsupported soldiers at the Thma Puok border who were at high risk of AIDS and alerted the authorities. Risk had to be addressed quickly or there was a risk of the epidemic reigniting.

Chapter Sixteen, Deadly gender imbalance, youth overlooked-meeting expert, Increase in injecting drug use, Farewell to Phnom Penh

Our technical working group was carrying out a Provincial situation analysis including the gender imbalance and powerlessness of women. Almost half of Banteay Meanchey women said they would not refuse sex even if their husband was HIV positive. Youth was an under serviced group despite teenagers having twenty percent of the abortions. Little research was done until Graham Fordham arrived. I met him in Phnom Penh. He was a social anthropologist with ten years’ experience in Thailand, and in 2003 he published a book on adolescent reproductive health and things changed. In Phnom Penh for the last time, I learnt about the increasing injecting drug use. Three years later up to one third of injecting drug users were HIV positive.

The Mekong

Chapter Seventeen Boeung Trakoun transformed, dengue, USAID and community support, farewelling friends and departure.

After a year, reproductive health services and education in Boeung Trakoun had been transformed. Sex workers were connected to health services and condoms, clinics were providing STI treatment and partner follow-up, condoms were available, chiefs had been educated, and videos sent to karaoke bars and the boxing club. A dengue outbreak threatened children and sometimes expatriate’s lives. USAID provided community support through KHANA the national NGO network and the local NGO network. Following training and a needs analysis a local NGO was given US$14,000 for six villages. Sarin began working at the Poipet Clinic, sponsored by ZOA. She and her team also did outreach. After a party, I left in mid July 2001.

Chapter Eighteen, Personal aftermath, Cambodia now, finale

I crashed on return to Australia as my visitor prophesied. I was offered a job in Laos but stayed as my father was in the early stages of Alzheimers. However I attended and presented at the Asian Pacific International AIDS conference in October with my counterpart Eap. I was given a certificate of recognition by a Cambodian Princess and later a similar one from the Australian Government. I returned to nursing and three and a half years later flew to Liberia to work with MSF.

Cambodia continued its battle with HIV/AIDS and in 2010 received an award from the UN. HIV prevalence was 0.8%, and over 90% of HIV positive patients were receiving antiretrovirals. In 2018 TB killed more people than AIDS, 6,500 compared to 1,300 AIDS deaths. Donors were assisting with surveys and the introduction of improved TB testing.

Poverty has decreased, income has increased five-fold and life expectancy risen from 58 in 2000 to 70 in 2022.

My 18 months in Cambodia was an extraordinary experience. It highlighted how little I knew about the world and myself. The epidemic became a personal challenge, and I fought it with everything I had. I fought it with a great heart, and that is what the country asked of me.

My plan for the Solomons later this year

I have a trip booked for six weeks from early August. After seeing the family in Arosi, Makira I’m planning to speak to women, both rural and urban working in many different fields.

Through contacts’ including my son Brian and Linked In, I’ve noticed an increasing number of successful businesswomen and women farmers exporting niche products such as ginger, noni juice, dried fruit, cacao, and coconut.

Some women are working with the Ministry of Lands recording customary land boundaries, while others are becoming accountants and providing online advice.

There is a lot to catch up with in health too, with more emphasis on Chronic Diseases including the appointment of Chronic Disease Nurse Coordinators. Nurses are also now trained to care for the feet of diabetic patients to reduce the number of amputations. As well as treatment for these diseases are messages about the dangers of the western diet, particularly sugar, reaching the rural areas? Are Church Women’s groups a part of this.

Following the introduction of DV legislation it would interesting too, to speak with counsellors, child safety practitioners and female police.

In education female teachers in rural training centres are being upskilled. Are there computers in these centres and are they available to the villagers. Are there computers in rural primary as well as secondary schools? Do village children have access to reading material from an early age, including in their local language?

How are women engaged in climate change and preparing for the growing intensity and number of cyclones, floods, and droughts? How is the problem of decreasing land availability and declining fertility being addressed? How are women in environmental NGOs supporting village women who oppose logging or would like to form protected areas.

There are lots of questions and maybe there will be stories, not only for me, but the local media, including the media company run by a woman.

On the boat to Kira Kira from Tawatana with Henry and Ida

Pounding nuts for cassava pudding

Baking the cassava pudding

A preview of my completed manuscript “Cambodia 2000: The AIDS year”

After watching my sister Sue die at the age of 41 from a melanoma my own life seemed meaningless. It was August 1998. At her deathbed with my parents Gill and Ray and my younger sister Lil, I sensed a very powerful spiritual force. I also felt the presence of my brother Pete and his wife Wendy, who had died with two of their three children in a car accident over ten years earlier.

I continued grieving. Night after night I couldn’t sleep and stood at my window overlooking the park waiting for dawn. One night I woke after a vivid dream. I had seen six Asian village women wearing long cotton skirts, their faces darkened by the sun, standing in the shade near a dry riverbed. They begged me to come over. They were terrified because their husbands were dying. If they refused sex they were beaten.

I woke knowing I had to find them. I’d had dreams like this before and they’d always been right. I began to look for volunteer positions and found one for a nurse with Australian Volunteers International (AVI) in Cambodia. They had the fastest growing AIDS epidemic in Asia. I’d worked as a nurse and journalist in the Solomons and faced multiple challenges. I applied, was accepted, and began to learn all I could about HIV/AIDS in Cambodia.

It was a crisis threatening to overwhelm their health system and economy and threatening to become the new killing field. It was fuelled by brothel-based sex workers with from one third to one half testing HIV positive. A survey found that sixty percent of Cambodian men regularly visited brothels (Agence France Press, 1999).

The women in the dream were right. It was passing into the general population with the HIV positive prevalence rate between 3 to 4 %. The figures from the year before showed 160,000 people were infected including 2,200 children. There were already over 5000 AIDS orphans (Godwin, 2000).

The weeklong orientation course in Melbourne was depressing. Another volunteer, a doctor, said he would never volunteer for such a position. There would be few working hospitals, very few laboratories and no antiretrovirals. What could I do? He was right but I went anyway.

I met Dr Tia Phalla when I arrived in Phnom Penh in March 2000. In 1991 he recognised AIDS had the potential to destroy his country as Pol Pot had done earlier. He formed the National AIDS Committee, spoke with communities countrywide and advocated with leaders. He became the Secretary General of the National AIDS Authority (NAA). (Buler 2006).

He asked me to go to Poipet, on the Thai border, where AIDS was growing faster than anywhere else. The poor from all over Cambodia migrated there. There was a high tax on goods carried by trucks across the border, so human labourers carried goods between the trucks on either side.

“They think its heaven, but it’s hell,” he said.

Could I make a difference? I had little confidence but at least I’d try.

This happened over twenty years ago so why does this story matter now?

There was a global resurgence of HIV/AIDS while the world was diverted by COVID.

In 2021 around 1.5 million people were diagnosed with HIV/AIDS and approximately 650,000 died (UNAIDS, 2022). In Fiji in 2021 there were 151 cases and 25 deaths (Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services, 2022).

The UNAIDS Director for the South Pacific based in Fiji, Renata Ram, described it a s ticking timebomb (RAM, 2022). The UNAIDS Global update for Fiji estimated 1400 people were HIV positive, but only 57% knew their status and only 45% were on antiretrovirals. The virus was spread by injecting drug uses and risky sex with multiple partners. They met online first and then again at a secret location.

As a Pacific Hub risky trends in Fiji tend to be exported, including by students attending the University of the South Pacific (USP). Ms Ram recommended countries in the region upgrade surveillance, support community education and mobilisation, and introduce harm reduction measures.

The Australian Government supported this response by announcing an extra $12million for new HIV prevention and treatment options in communities and countries in the Pacific and South East Asia the day before World AIDS Day on 1 December 2023. As Professor Darryl O’Donnell, the CEO of Health Equity Matters, one of the three partners alongside the Australia Government and UNAIDS, said “The most effective way to treat and prevent HIV is to empower the people who most feel its impact (Wong& Conroy, 2023).

This is community mobilisation, not only the central intervention in the Cambodian response, but initially the only one. And yet that country was one of only three countries worldwide in 2000 that turned their epidemic around.

With a young Cambodian girl

A Cambodian food stall

In the MSF hospital in Thma Puok

Poipet

An underused clinic on the Cambodian/Thai border

Chocolate Artisan, the Sydney chocolate factory and the destination of cacao from Makira Gold.

After writing Frigate Birds I sent a copy to Jessica Pedemont, Brian’s partner in South Pacific Cacao. A chef since 17, with much of working life devoted to chocolate products, Jessica describes herself as a chocolate evangelist and runs a business Chocolate Artisan from Ramsay Street in Haberfield Sydney.

Jessica loved the book and sent back a big box of goodies and invited me on a tour of the factory whenever I was in Sydney. In late January a friend and I flew down to see the Kandinsky and Ramses II exhibitions and Jessica’s factory.

After writing Frigate Birds I sent a copy to Jessica Pedemont, Brian’s partner in South Pacific Cacao. A chef since 17, with much of working life devoted to chocolate products, Jessica describes herself as a chocolate evangelist and runs a business Chocolate Artisan from Ramsay Street in Haberfield Sydney.

Jessica loved the book and sent back a big box of goodies and invited me on a tour of the factory whenever I was in Sydney. In late January a friend and I flew down to see the Kandinsky and Ramses II exhibitions and Jessica’s factory.

Jessica and Fiorella in front of reception at factory

Brian buys high grade cacao beans from farmers in the Solomons and transports them from the Solomons in green grain pro bags which protect them from pests and moisture. Although the farms are organic some do not have official organic certification while World Vision has supported others to get it. When the beans arrive in Brisbane Brian checks and grades them and sends the high quality beans to Jessica in Sydney via courier.

All the beans used are dried in solar dryers. Many Solomon Island cacao farmers still dry their beans in smoky wood fired kiln dryers (like copra dryers), however the beans produced are of lesser quality as the smoke taints them and they are not dry enough.

When the bean arrive they are roasted and Jessica uses the Italian Unox oven (below) the most widely used oven in the world for roasting cacoa beans

Below are trays of Lucy’s beans which Jessica said were of very good quality. Lucy is a cacao farmer in Makira.

The cacao beans then go into a winnower which separates the husk from the nibs, or pieces of cacao beans.

The husks go into this bag. Husks are similar to the bran produced after wheat is milled. Jessica uses them in Xmas cakes and biscuits and they can be used to make beer.

The nibs come out on the other side of the winnower and are then ground.

The grinder weighs 500kg and the nibs are ground between two big 45kg granite wheels.

The chocolate still needs to be tempered. Jessica describes this as the art of heating and cooling the chocolate, so all the crystals have the same melting point. The chocolate is smoother, and the flavours are released at the same time.

Margaret and the tempering machine

Above is an engrossing machine which coats nuts with chocolate including macadamia nuts.

Solomon Island products which are already being sold include ngali nuts.

In PNG these nuts are known as galip nuts.

The Solomons also exports dried pineapples, bananas and pawpaws.

Some of these products are sold at the international airports in the Solomons and on Solair flights.

Jessica enjoys experimenting and developing new products. She has a keto bar for diabetics and is experimenting with the use of chocolate and kava.

She has a lot of visitors from all over the Pacific visiting her factory and is very impressed the quality of some of the Pacific ingredients, particularly the wild turmeric from Fiji which has a much higher percentage of curcumin, over four times as much as the regular turmeric which is 4%.

She also provides practical support for some Pacific businesses.

Diana Yates, Tommy Chans wife has a cocoa business Cathliro in the Solomons and is setting up a chocolate factory. Tommy Chan is the owner of Honiara Hotel. Diana sent her daughter and a senior employee to work in Jessica’s factory for a week in 2023. Her business also developed a protein bar for athletes at the South Pacific Games. When the hydropower from the Lunga Dam is available in a few years it will finally provide Honiara with a reliable source of electricity, boosting not only Diana’s business but many others.

Margaret, Fiorella and Jessica having fun

Launch 6th May Brisbane

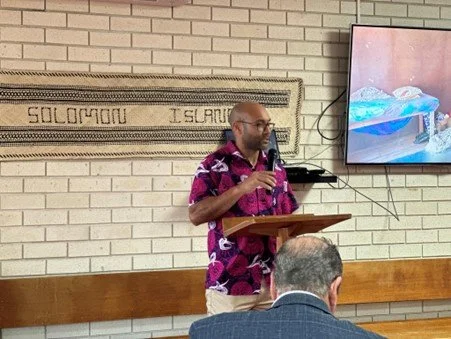

Brian Atkin was MC,

Speaker Joe Tooma, CEO of the Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation for 14 years

and Margaret Atkin

These are excerpts from the second session, 4 to 5pm. There was an earlier session which Gill Lycette, Margaret’s mother attended with 15 others which ran from 2.30 to 3.30pm.

Both John Atkin and George Atkin sent their best wishes for the launch.

Brian as MC

Brian began by saying:

He had watched his mother keeping diaries, newspapers and letters in various sheds for thirty years and always wondered what she would do with them.

Brian was hoping that when his mother retired she would slow down, but instead she began editing her father (R R Lycette’s) novels, Fragrant Harbour was subsequently published by Sid Harta and copies Red Dragon in a Green Circle printed. Margaret then went on to write her own memoir, Frigate Birds after discovering her father Ray had kept all her letters from the Solomons.

When Brian asked why she was spending so much time on this work Margaret replied that both she and her father had important stories to share. She was following in the footsteps of her grandfather Ernest Lycette who wrote a memoir about his time as a solider and officer in the First World War,

I am now extremely grateful Mum wrote this book, Brian said. It will pass down to my children and their children.

I have travelled with mum to the village in the Solomons many times. She is happiest and most home there, speaking pidgin.

I helped mum get Gardasil, the cervical cancer vaccine to the Solomons.

It was a remarkable achievement and will continue to be life saving for many people.

Joe will speak further about this.

So thank you Mum for your passion, your love for the Solomons and your great resilience.

Margaret listening

Joe than spoke

“Welcome to the launch of Margaret Atkin’s fascinating book, Frigate Birds.

For me Frigate Birds is a remarkable, raw, engaging and honest story of a very important period in the development of the Solomons and in Margaret’s personal and generous life’s journey. It gives us a real bird’s eye view, a Frigate Bird’s view of Australia’s strategically important neighbour. I will briefly comment on the issues Margaret engaged so strongly with, exploitation of people and resources, a fledgling democracy, and the battle to beat cervical cancer.

Exploitation of people and resources

As with many indigenous peoples who came into contact with empire building nations, the Solomons was exploited, beginning with blackbirding when men and boys were taken on a one -way journey to be forced indentured workers or as good as slaves.

There are still nations corporations and unscrupulous individuals taking advantage of the fisheries, minerals, wealth and native timber, so depriving the community of their heritage. It causes misery, poverty, division, distrust and discontent.

Margaret describes the disaster that was logging in her part of paradise, destroying the environment, breaching logging conditions, logging on private land they had no rights to log, and polluting local rivers and water supplies. She also writes about the villager’s real fears that the foreign logging workers might bring AIDS with them, because of their exploitation of young locals.

Complaints to the police and authorities by landowners and villagers were ignored because of the influence the loggers wielded over authorities and politicians. Margaret did something about it, giving the locals hope and belief they too could be heard and respected.

A fledgling democracy.

The Solomons is a young democracy and there have been teething problems. This can be expected in a nation built for countless generations around ethnicities, village groups and ‘wontok.’

As well as being a nurse and a midwife, Margaret trained as a journalist and wrote stories of community concern and interest and for a time ran the newspaper, the Solomon Toktok. Her work made sure the community became aware of and were educated about important issues like politics, crime, government budges and finances and she was outspoken about women’s issues and domestic violence. Most importantly the newspaper was valuable to her community because it was independent, trusted and unbiased news.

The battle to beat cervical cancer

Proudly I can speak personally about Margaret’s remarkable work in fighting cervical cancer because this is how I came to meet her.

It took something like seven years of constant meetings in the Solomons, talking and gently pushing almost anyone we could find, before we achieved the dream of finally having a national cervical cancer vaccination program for Solomon Island schoolgirls. This was nearly ten years after the Australian schoolgirls vaccination program had begun.

Without Margaret and her son Brian Atkin driving the project and earning the respect and cooperation of so many people this remarkable outcome would not have happened.

Why does it matter?

Cervical cancer is the biggest cancer killer of women in many developing countries and the Solomons is no exception. Yet with vaccination and screening it is almost entirely preventable as we have shown in Australia in the last 20 years. I can confidently say after my experience of programs in several developing countries that cervical cancer rates are likely to be between ten and twenty times Australia’s rates.

We all hoped after the Pacific Leader’s Forum in Port Moresby in 2015 when their official communique recognised cervical cancer as a serious problem that needed resources and expert technical assistance that the situation would change. But so far there has been more talk than action.

There would be a huge benefit if a Pacific Coalition, supported by Australia and NZ, was formed to eliminate cervical cancer. It would only need a few million dollars (insignificant in Australia’s budget) to establish this coalition so that it becomes a rare cancer.

I want to leave you with a short quote from ‘Frigate Birds’ which captures Margaret’s passion. Speaking of her village she says

“In that place I realise who I am and what I have become. I understand what really matters and what doesn’t.

Margaret thank you for your passion, your kindness and your brave determination. Your wonderful book is a joyful, life-affirming ‘must read’.

Joe and Oti, President, Solomon Islands Brisbane Community

Margaret Excerpts from my speech.

Over forty years I have witnessed a lot of change, much of it detrimental and avoidable. This included unregulated logging, over fishing and over population. From my sources I could identify the moment when the wrong decision was made, or no action taken. This applies especially to logging and the birth rate, which in the seventies and eighties was one of the highest in the world.

The change of life style and the cash economy is now causing an epidemic of chronic disease which includes diabetes, heart disease and stroke. After the tensions (1998 to 2003), social breakdown and the increased use of marihuana and other drugs, there was a rapid rise in mental illness. During my visit in October last year to Makira and Tawatana I could see the effect these changes were having at the village level.

However the status of women is improving, as better educated women provide leadership and services. There is finally an increase in the use of contraception, with younger women, including those in rural areas, preferring smaller families.

Corruption has plagued the Solomons since pre-independence, and it continues to sap the country. Visiting Honiara last year, the Chinese presence was very evident. They own much of the land and many of the buildings. However new Chinese arrivals seem less interested in the provinces, where life is tougher.

Despite the problems, some of the happiest days of my life have been spent in the Solomons, especially in Tawatana. Returning to Tawatana last year I was again called Margie, or Auntie by many people. The wonderful nurse at the clinic tried to persuade me to retire there. She said she had heard people talking about me while they waited on the veranda.

I told her it was impossible. The village environment is tough, and growing tougher, especially for a 69 year old European.

There are no fish, with overpopulation the land is overused, less fertile and the gardens further away. The water supply is inadequate and intermittent. It is unrelentingly hot, there is no refrigeration, no air conditioning, poor internet connection, and a poor selection of food, mainly tins, flour, white rice, sugar and soft drinks in the village shops. I wondered too, what my family would say about such a decision. But part of my heart will always be there, and I know it is the same with Brian.

Martin Hadlow then spoke. He was a journalist at the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation (SIBC) in the early eighties, while Margaret was working as a journalist and then editor of the Toktok.

The Solomons Toktok was a very important weekly during its time. I admired the courage of George and Margaret Atkin who ran the paper.

Honiara was a very small place, with a small commercial base and most of the advertising went to the SIBC which had national coverage.

They also had competition from the Solomon Star which was founded after the government newssheet the Solomon Drum was sold to John Lamani for one dollar. He left the SIBC taking the best journalists with him. There really wasn’t room for two newspapers in the Solomons.

I hope to read about the famous courtcase when you were charged with prejudging a case. I want you to know that all the expatriates were on your side and at the G Club we urged the Chief Justice to be gentle with you. He was, just giving you a slap on the wrist.

Margaret replied. This is the first time I have ever been thanked for my work as a journalist there. It is very moving.

Solomon Island’s group. Clive Moore Prof of History UQ, Aka, treasurer SIBC, Margaret, Brian, Oti President of SIBC and her son, Lawrence, Malcolm and Logan.

Tawatana - the first three days

I arrived by canoe in the late afternoon. We left Kirakira in the morning and should have arrived three to four hours later. But the canoe had broken down and needed a gear box change, which was providentially provided by a relative Henry, who came to investigate when he saw us limping past, clearly in trouble.

George had given up waiting on the beach and gone back to the house on the plateau.

I arrived by canoe in the late afternoon. We left Kirakira in the morning and should have arrived three to four hours later. But the canoe had broken down and needed a gear box change, which was providentially provided by a relative Henry, who came to investigate when he saw us limping past, clearly in trouble.

George had given up waiting on the beach and gone back to the house on the plateau.

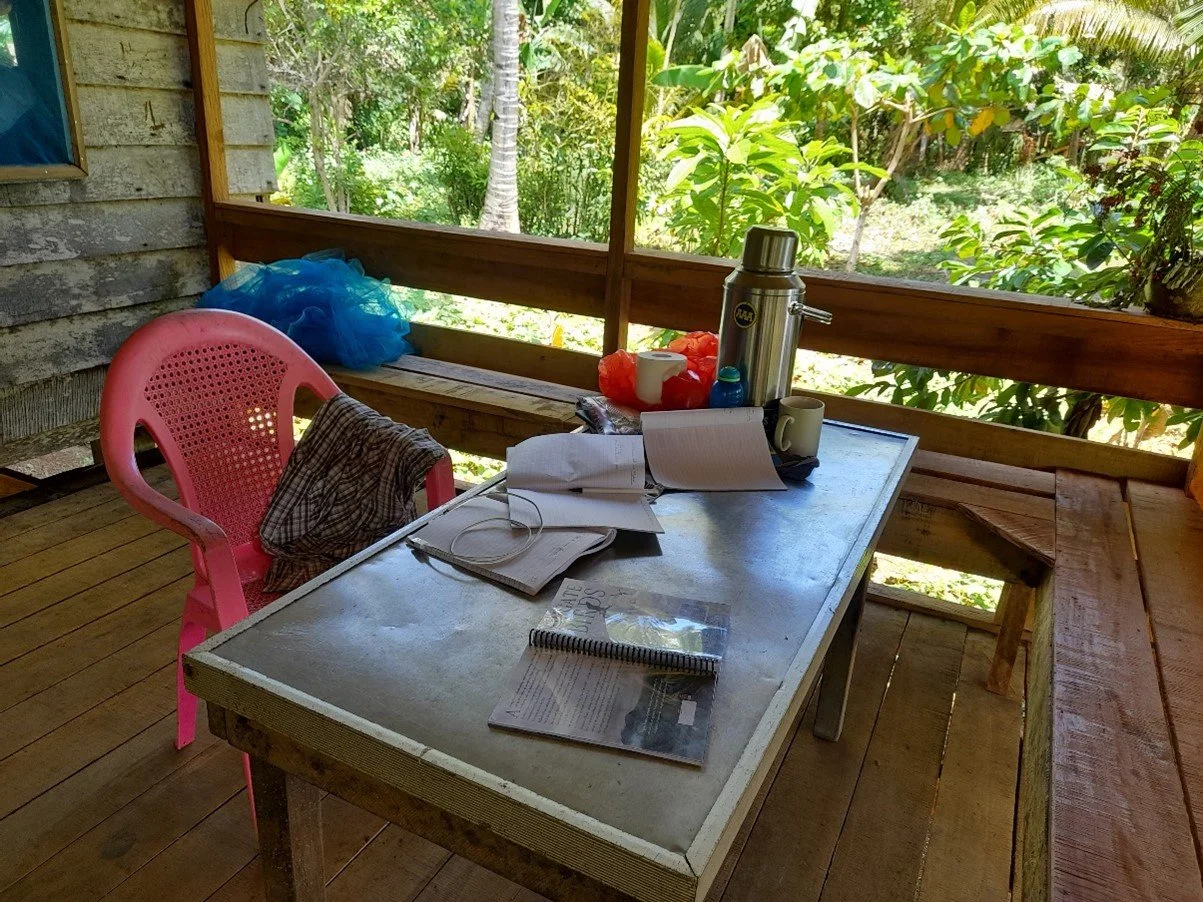

On the new back veranda was a table with a cloth.

This I learnt was for a mother’s union gathering that evening.

They hadn’t planned it for me but for George. It was part of their weekly program of care for the elderly and disabled in the village, where they provided a meal and companionship.

It was a great evening. We ate well, ony my farewell party five weeks later compared with it, and the women truly welcomed me. We had prayers and short speeches, and as they left I hugged them.

The night though was nightmarish. My newfangled lilo wouldn’t blow up, and finally pitying me, George lent me his mattress. There was a strange arrangement where the solar light shone brightly through the open doorways until 2am. Finally after moving to a room which had two window and a faint breeze, I finally slept.

The next day help appeared in the form of a relative and neighbour who built a bed level with the windows, and my friend Nunuau who lent me a nice mattress, pillow and some linen.

I was sick with a constantly running nose, and attributed it to the dust which had been absorbed into the bare timber walls and floor. Eunice and Nunuau promptly set about heating water and cleaning the floors and wall, one room at a time. George believed the sickness as a virus, and on reflection he was right. Many others were ill including a student who came to interview him, and coughed and spluttered. Miraculously he did not get sick.

George’s bed in the main room. Somehow he had learnt to sleep with the solar light on until 2am.

The dining table on the veranda had been borrowed. Instead we ate at a coffee table in the main room.

In the kitchen you can just see the burner, given to George by his journalist friends after he lost everything in a rest-house fire in Kirakira in 2021. You can just see the sink. Unfortunately it was attached a tank which hadn’t been cleaned for years. While I was there it was cleaned.

Everyday we would sit on the veranda and work on the book.

Eunice bought us food. We had not yet managed to work out how to cook in the leaf kitchen George’s brother Leslie had built for him.

Behind is the toilet and laundry.

Every day George would check the termite tracks. When I got back to Honiara I tried to send back some proper treatment but it was expensive and was not likely to work. Previously we had used dirty engine oil around the stumps, the local treatment. The house was built almost 20 years earlier in 2004.

The other threat to the house, as I realised when there was a storm was the trees around the house.

Finally, on the third day, feeling a little better I got back to the beach where I arrived.

A lot of the sand has gone from the beach. It has been taken to the school, for concrete. Others have taken the coral for floors and paths.